Ibadan Against the Fulani Jihad

I toss and turn in my bed like bacon sizzling on a grill. Without the exhaustion of a 27 hour journey which had made sleeping easy the night before, tonight the eight hour time difference has my body thinking 10pm is 2pm. The mosquito netting around the bed is gently illuminated with the dim golden glow of the somnolent city -- I leave the blackout blinds open, preferring city light to waking up in tomb-like darkness. Finally I drift to sleep, and let us once again suppose I had strangely accurate meflequinated dreams:

It’s 1840 and the Fulani Jihad that had pursued the Zazzau to Abuja has spread across Yorubaland as well. The once mighty kingdom of Oyo is collapsing before the onslaught, the Fulani horsemen thundering indomitably across the open savannas. The surviving Yoruba warriors flee southward, where the land gradually becomes more forested and increasingly is almost impassable scrub off the trails and cleared ground. Here on the edge of the forest they gather into a town built on a rocky ridge on top of a hill, called Eba Odan or “by the edge of the forest.”

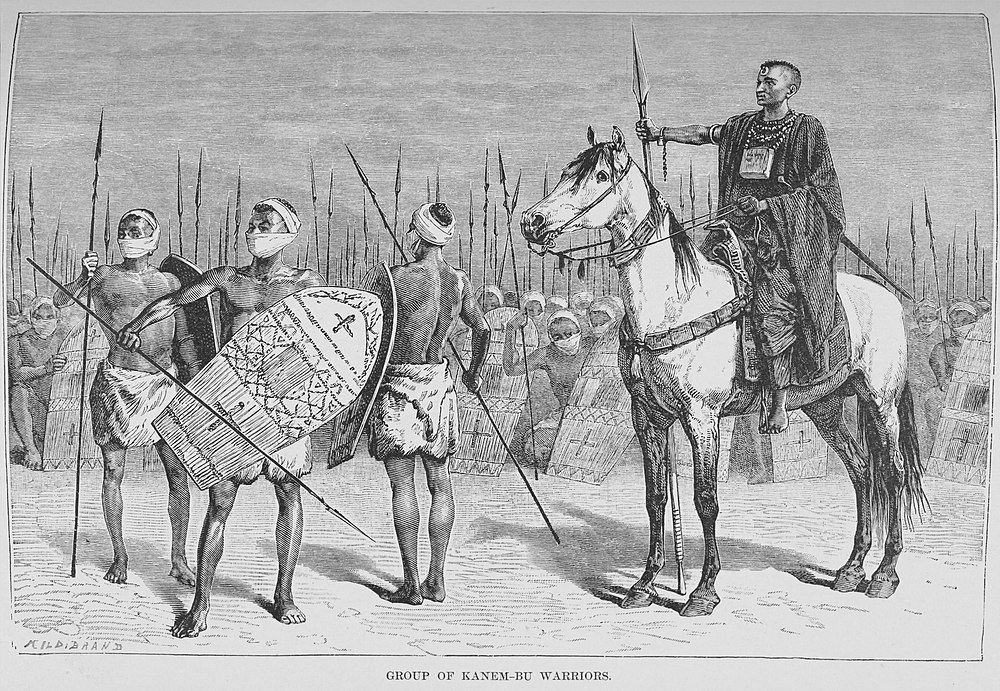

The ragged warriors make their way up the trails and through the narrow entrances of the three concentric palisade walls of the town. There are cavalry on tired horses, with their lances and swords, which resemble a heavy cutlass, slightly curved and sharpened only on one side), and infantry with their four-foot hide shields and spears. As well as the traditional armaments, some warriors in the town sit cleaning guns acquired in trade with Europeans in Lagos to the south. Refugees from the north bring with them alarming tales of the tides of war. The emir of the northern Yoruba town of Ilorin has defecting his allegiance to the Sokoto Caliphate, taking with him much of the Oyo cavalry, and the capital of old Oyo Town has been razed by the Fulanis.

The chief warriors gather in the town square. The long wood-and-thatch houses of the chieftains surround the square, and some palm trees wave at the sky. The foremost warriors are the Eso, a rank bestowed upon only a few dozen cavalrymen who have proven their prowess and ability to abide by the code of honor. These knights of the Yoruba gather in a circle surrounded by the many other warriors as their leader, the Bashorun, outlines his plan to make a stand here against the Fulani.

“The high king, the Alaafin, as you know has charged us with defending what remains of the Oyo Kingdom and defeating the Fulani invaders,” the Bashorun addresses the gathered warriors.

“Eso Elepo, I would like to appoint you as the Ibalogun, commander of our forces” he says turning to one of the foremost warriors. The assembled crowd cheers their approval, but when the noise dies down Elepo is shaking his head.

“My own name is enough for me, I wish no title beyond eso, like my father before me.”

They try to convince him but to no avail. And so the Bashorun instead bestows the title of Ibalogun on another warrior, eso Oderinlo.

Look mate if ancient Yoruba warriors can wear masks you can too

The Fulani armies of the Sokoto Caliphate close in on Ibadan, past the outlying villages of Ilobu and Edo, and are funnelled into ever narrower paths by the thickening forest. Suddenly from the thickets around them there is the roar of guns, followed by the screaming onrush of Yoruba warriors through the gunsmoke and shrubs, led by eso Elepo, hurling their spears and swinging their heavy swords. The Fulani horses rear up and the warriors brandish their lances but there’s no room to maneuver.

The Ibadans pursue the Fulanis to the village of Edo, and in their bloodlust are prepared to raze it before Elepo and his men stop them, reminding them that the Edoans are their people. They advance further to Ilobu and again Elepo holds back the wild warriors from destroying it. In gratitude the people of Ilobu heap gifts in front of Elepos tent.

As the victorious warriors troop back through Ibadan to the central square, the gathered crowds cheer for no one more than edo Elepo. When they are gathered before the Bashorun the Ibalogun complains that Elepo is taking credit beyond his station for their victories, and demands he prostrate himself before him.

“I prostrate myself before no one but the Bashorun!” Elepo objects. The Ibalogun scowls darkly at him but Elepo is too powerful to punish.

“What is your plan now?” the Bashorun asks

“We will advance towards Osogbo across the Osun river” the Ibalogun proposes, “to push the Fulani entirely out of this area of Yorubaland. We can’t compete with their horsemen on the open plains during daylight but we will only seek to meet them by night.”

“Yes this is a good plan will you take the entire army?” the Bashorun asks.

“No,” says the Ibalogun with a sneer, “Eso Elepo can remain here with his thousand men.”

“You can’t win without Elepo!” blurted out one of Elepo’s supporters, eliciting a glare from the Ibalogun.

A warrior comes galloping up the trail from Osogbo. There are cuts on his muscular arms that look like they’ll scar but he sits straight and proud in his saddle.

“What news??” people call to him as he enters the palisade gates, “were you victorious?” but he stares straight ahead expressionlessly as he rides up the streets to the central square and Bashorun’s house. There he dismounts and enters. A short time later the Bashorun emerges, looks around the crowd that has gathered, expressionlessly, and then breaks into a grin to announce

“They have won a great victory! The Fulani tide has been turned back!” and the crowd broke into loud cheers.

A little later, however, when the Bashorun saw eso Elepo he took him aside.

“The messenger reports that the war chiefs want you to leave, with the glory they have now won you cannot stand against them.”

“You won’t stand up for me? Remember when I alone stood up for you after the Ota War, when the Bashorun Lakanle and his war chiefs ordered that you would not be permitted to return?”

“Yes, yes, my friend, I remember. “ Bashorun Oluyole says putting his hand on Elepo’s shoulder, “listen, just temporarily go to Ipara until I can smooth things out here.”

Elepo looks his friend in the eye and knows he’ll never return but nods resignedly.

Ibadan in the 1850s

So there you have it, the true story of how Ibadan defeated the Fulanis of the Sokoto Caliphate, as best I can piece it together. I did I ridiculous amount of research to write these thousand words, reading Captain Hugh Clapperton's 1829 account of traveling in the region and Rev Samuel Johnson's 1897 "History of the Yorubas." This latter I found very interesting reading as he seems to have had access to an intimate knowledge of his people's history for the past century complete with the kind of interpersonal rivalries and friendships that quite bring it alive. This story of Elepo, who refused a title and then angered the other war chiefs by outshining them is jsut one of many interesting tales.

I was particularly intrigued to learn that the Yorubas had an essentially "knightly" class of elite mounted warriors devoted to a warrior's code, the "eso." This as I mentioned is a first draft, as I continue to tweak this I want to continue to shape it to be reminiscent of an Arthurian tale of knights.

Anyway, please let me know what you think of these tangents into historical fiction. Are they working? Are they a weird distraction?

no subject

no subject

no subject

no subject

no subject

no subject

no subject

Art source: https://archive.org/details/yorubacountry00hinduoft/page/n11/mode/thumb?view=theater (Anna Hinderer)